Greetings! I would like to welcome everyone to the Covenant of Babylon blog page. If this is your first time here, please feel free to review some of our previous articles and share your insights and comments. Stay Blessed.

THE TREE OF LIFE

A stylized tree with religious significance occurs as an art motif in 4th-millennium Mesopotamia, and, by the 2nd millennium B.C., it is found everywhere within the ancient Near Eastern provinces, including Egypt, Greece, and the Indus civilization.’ The meaning of the motif is not clear, but its over-all composition strikingly recalls the Tree of Life of later Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Buddhist art. The question of whether the concept of the Tree of Life actually existed in ancient Mesopotamia has been debated.

About the middle of the 2nd millennium, a new development in the iconography of the Tree becomes noticeable leading to the emergence of the so-called Late Assyrian Tree under Tukulti-Ninurta I. With the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, this form of the Tree spread throughout the entire Near East and continues to be seen down to the end of the 1st millennium. Its importance for imperial ideology is borne out by its appearance on royal garments and jewelry, official seals, and the wall paintings and sculptures of royal palaces, as in the throne room of Ashurnasirpal II in Calah, where it is the central motif.

The hundreds of available specimens of the Late Assyrian Tree exhibit a great deal of individual variation show that the motif and most of its iconography were inherited from earlier periods. Nevertheless, its features stand out even in the crudest examples and make it easy to distinguish it from its predecessors.

Essentially, it consists of a trunk with a palmette crown standing on a stone base and surrounded by a network of horizontal or intersecting lines fringed with palmettes, pinecones, or pomegranates. In more elaborate renditions, the trunk regularly has joints or nodes at its top, middle, and base and a corresponding number of small circles to the right and left of the trunk. Animal, human, or supernatural figures usually flank the tree, while a winged disk hovers over the whole. Even the most schematic representations are executed with meticulous attention to overall symmetry and balance.

THE TREE: ITS SYMBOLISM AND STRUCTURE

What did this Tree stand for, and why was it chosen as an imperial symbol? There is considerable literature on this question, but despite the most painstaking iconographic evidence, on the whole, little has been explained. This is largely due to the almost total lack of relevant textual evidence. The symbolism of the Tree is not discussed in cuneiform sources, and the few references to sacred trees or plants in Mesopotamian literature have proved too vague or obscure to be productive.

Two fundamentally important points have nevertheless been established concerning the function of the Tree in the throne room of Ashurnasirpal’s palace in Calah. Firstly, Irene Winter has convincingly demonstrated that the famous relief showing the king flanking the Tree under the winged disk corresponds to the epithet “vice-regent of Assur” in the accompanying inscription. Clearly, the Tree here represents the divine world order maintained by the king as the representative of the god Assur, embodied in the winged disk hovering above the Tree.

Secondly, it was observed some time ago that in some reliefs the king takes the place of the Tree between the winged genies. Whatever the precise implications of this, it is evident that in such scenes the king is portrayed as the human personification of the Tree. Thus if the Tree symbolized the divine world order, then the king himself represented the realization of that order in man, in other words, a true image of God, the Perfect Man. If this reasoning is correct, it follows that the Tree had a dual function in Assyrian imperial art.

Basically, it symbolized the divine world order maintained by the Assyrian king, but inversely it could also be projected upon the king to portray him as the Perfect Man. This interpretation accounts for the prominence of the Tree as an imperial symbol because it not only provided a legitimation for Assyria’s rule over the world, but it also justified the king’s position as the absolute ruler of the empire.

The complete lack of references to such an important symbol in contemporary written sources can only mean that the doctrines relating to the Tree were never committed to writing by the scholarly elite who forged the imperial ideology but were circulated orally.

The nature of the matter further implies that only the basic symbolism of the Tree was common knowledge, while the more sophisticated details of its interpretation were accessible to a few select initiates only. The existence of an extensive esoteric lore in 1st and 2nd-millennium Mesopotamia is amply documented, and the few written specimens of such lore prove that mystical exegesis of religious symbolism played a prominent part in it.

THE SEPHIROTIC TREE

Mesopotamian esoteric lore has a remarkable parallel in Jewish Kabbalah, and, more importantly from the standpoint of the present topic, so does the Assyrian Tree. A schematic design known as the Tree of Life figures prominently, in both, practical and theoretical Kabbalah. In fact, it can be said that the entire structure of Kabbalah revolves around this diagram, a form which strikingly resembles the Assyrian Tree.

The Sephirotic Tree derives its name from elements called Sephiroth, literally “countings” or “numbers,” represented in the diagram by circles numbered from one to ten. They are defined as divine powers or attributes through which the transcendent God, not shown in the diagram, manifests Himself.

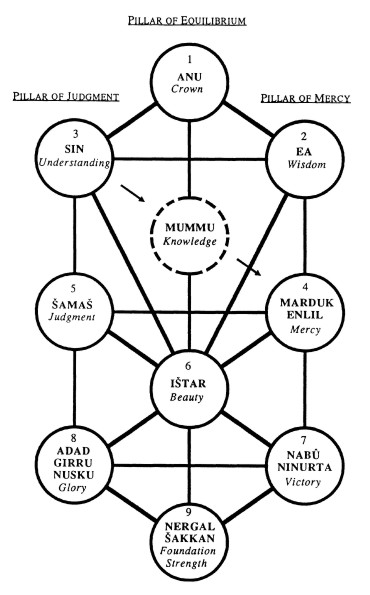

Each has a name associated with its number. The Tree has a central trunk and horizontal branches spreading to the right and left on which the Sephiroth are arranged in the symmetrical fashion: three to the left, four on the trunk, and three to the right. The vertical alignments of the Sephiroth on the right and left represent the polar opposites of masculine and feminine, positive and negative, active and passive, dark and light, etc. The balance of the Tree is maintained by the trunk, also called the Pillar of Equilibrium.

Like the Assyrian Tree, the Sephirotic Tree has a dual function. On the one hand, it is a picture of the macrocosm. It gives an account of the creation of the world, accompanied in three successive stages by the Sephiroth emanating from the transcendent God. It also charts the cosmic harmony of the universe upheld by the Sephiroth under the influence of the polar system of opposites. In short, it is a model of the divine world order, and in manifesting the invisible God through His attributes, it is also, in a way, an image of God.

On the other hand, the Sephirotic Tree, like the Assyrian, can also refer to man as a microcosm, the ideal man created in the image of God. Interpreted in this way, it becomes a way of salvation for the mystic seeking deliverance from the bonds of flesh through the soul’s union with God. The arrangement of the Sephiroth from the bottom to the top of the diagram marks the path which he has to follow in order to attain the ultimate goal, the crown of heaven represented by the Sephirah number one, Kether.

Tradition has it that the doctrines about the Tree were originally revealed to the patriarch Abraham, who transmitted them orally to his son. In actual fact, the earliest surviving Kabbalistic manuscripts date from the 10th century A.D. It is generally agreed, however, that the “foundation stone” of Kabbalism, the Sepher Yetzirah, was composed sometime between the 3rd and 6th centuries, and the emergence of Kabbalah as a doctrinal structure can now be reliably traced to the 1st century A.D.

The renowned rabbinical schools of Babylonia were the major centers from which the Kabbalistic doctrines spread to Europe during the high Middle Ages. Altogether, the Sephirotic Tree displays a remarkable similarity to the Assyrian Tree in both its symbolic content and external appearance. In addition, given the fact that it seems to have originated on Babylonian soil, the likelihood that it is based on a Mesopotamian model appears considerable. As a matter of fact, a number of central Kabbalistic doctrines, such as the location of the Throne of God in the Middle Heaven, are explicitly attested in Mesopotamian esoteric texts. The crucial question, however, is how the existence of the hypothetical Mesopotamian model can be proven, given the lack of directly relevant textual evidence.

THE ASSYRIAN TREE DIAGRAM

For the above reasons, I had for years considered the identity of the Assyrian and Sephirotic Trees an attractive but probably unprovable, until it finally occurred to me that there is a way of proving or rejecting it. For if the Sephirotic Tree really is but an adaptation of a Mesopotamian model, the adaptation process should be reversible, that is, it should be possible to reconstruct the original model without difficulty.

The basic elements of the Tree, the Sephiroth, are crucial in this respect. Their names and definitions strongly recall the attributes and symbols of Mesopotamian gods, and their prominent association with numbers calls to mind the mystic numbers of the Mesopotamian gods. They are, in fact, represented as angelic beings in some Sephirotic schemes, which is consistent with their definition as divine powers. Accordingly, in the Mesopotamian model they would have been gods, with functions and attributes coinciding with those of the Sephiroth.

Thus, I replaced the Sephiroth with the Mesopotamian gods sharing their functions and/or attributes. Most gods fell into their place immediately. We need no justification for associating Ea with Wisdom, Sin with Understanding, Marduk with Mercy, Samas with Judgment, Ishtar with Beauty, and Nabu and Ninurta with Victory (Netzach). Crown (Kether) was the emblem of both Anu and Enlil, but since in the 1st millennium Enlil was commonly equated with Marduk (just as his son Ninurta was equated with Nabu), the top most Sephirah naturally corresponds to Anu, the god of Heaven. Foundation (Yesod) corresponds to Nergal, lord of the underworld, whose primary characteristic, strength, is in Akkadian homonymous with a word for foundation, dunnu. For the identification of Daath with Mummu (Consciousness) and the number zero.

I had to resort to Tallqvist’s Akkadische Gotterepitheta to find that the only gods with epithets fitting the Sephirah of Hod (Splendor or Majesty) was the storm god Adad, the fire god Girru, and Marduk, Nabui, and Ninurta, the last three of whom already had their place in the diagram. Accordingly, this Sephirah corresponds to Adad and Girru, who share the same mystic number, and it is noteworthy that in the Bible the word hod refers to Jahweh as a thundering and flashing storm.

The last Sephirah, Kingdom (Malkuth), is defined as “the receptive potency which distributes the Divine stream to the lower worlds,” which in Mesopotamia can only apply to the king as the link between God and Man. The motif of the king as distributor of the Divine stream is repeatedly encountered on Assyrian seals, where he holds a streamer emanating from the winged disk above the sacred Tree. I have excluded this Sephirah from the reconstructed model because it breaks the compositional harmony of the Tree and because the king, though impersonating the Tree, clearly does not form part of it in Assyrian art.

Once the gods had been placed in the diagram, which did not take longer than half an hour, I filled in their mystic numbers using as a guide W. Rollig’s article “Gotterzahlen” in the Reallexikon der Assyriologie. For the most part, this was a purely mechanical operation; in some cases, however, I had to choose between two or three alternative numbers. The numbers shown are those used in the spelling of divine names in the Middle and Neo-Assyrian standard orthography, and all of them are securely attested. I should point out that the number for Anu, 1, is erroneously given as 60 in Rollig’s article. Of course, the vertical wedge can also be read 60, but in the case of Anu, “the first god,” the only reading that makes sense is 1, as we shall see presently. The ease with which the gods and their numbers fit into the diagram was almost too good to be true, and the insights obtained in the process were more than encouraging. Suddenly, not only the diagram itself but the Mesopotamian religion as well started to make more sense.

THE DISTRIBUTION OF GODS AND NUMBERS

Looking at the reconstructed diagram more closely, one observes that practically all the great gods of the Assyro-Babylonian pantheon figure in it, some occupying the same place because they were theologically equivalent. Only one major god is missing, Assur, for whom no mystic number is attested. This strongly suggests that this important god has to be identified with the winged disk over the Assyrian Tree from which the Divine stream emanates and, accordingly, is identical with the transcendent God of Kabbalah, Ain Soph.

As a matter of fact, the various spellings of Assur’s name can, without difficulty, be interpreted as expressing the idea of the One, Only, or Universal God, as well as the various qualities of Ain Soph. The solar disk through which he was primarily represented implies that his essential nature was light, as in Kabbalah. Of the gods found in the diagram, Anu, king of Heaven, occupies the crown; Ishtar, representing all female deities, occupies the middle; and Nergal, the lord of the underworld, the base of the trunk. The remaining gods are arranged to the right and left sides of the trunk in a corresponding way, with sons lined under their fathers. In other words, the tree is composed of three successive generations of gods appearing horizontally as interrelated trinities, to be compared with the triadic configuration of nodes, volutes, and circles of the Assyrian Tree. The lines connecting the gods exactly render the divine genealogies known from late 2nd and early 1st millennium texts. But that is not all.

The distribution of the mystic numbers in the diagram adds to it a dimension unknown in the Sephirotic Tree. Six of the numbers are full tens, all neatly arranged, in descending order, on the branches of the Tree: those higher than 30 to the right, the rest to the left side. The numbers on the trunk are not tens, and their arrangement is different: they begin with 1, as in the Sephirotic Tree, but the following two are not in numerical order. Does this distribution make any sense? Initially, we note that the numbers on the trunk, when added together, yield 30, the median number of the sexagesimal system. From the standpoint of number harmony, this tallies beautifully with the medium position of the trunk and recalls its Kabbalistic designation, the Pillar of Equilibrium. The position of the number 15 in the center of the diagram is justifiable from the same point of view.

On the surface, the numbers on the right and left of the trunk seem to upset the balance of the Tree because the numbers on the left are consistently smaller than those on the right. Yet, when one adds the numbers together, one obtains for each branch the same total (30) as for the trunk, the Pillar of Equilibrium. This is so because the numbers on the left side, according to the polar system of oppositions governing the Tree, are negative and thus have to be subtracted from those on the right side. The sum total of the branches and the trunk (4 x 30 = 120) added to the sum total of the individual numbers (1 + 10 + 14 + 15 + … + 60 = 240) yields 360, the number of days in the Assyrian cultic year and the circumference of the universe expressed in degrees.

In all, it can be said that the distribution of the mystic numbers in the diagram displays an internal logic and, remarkably, contributes to the overall symmetry, balance, and harmony of the Tree. All this numerical beauty is lost with the decimal numbering of the Sephirotic Tree, which only reflects the genealogical order of the gods. The fact that the numerical balance of the Tree can be maintained only on the condition that the left-side numbers are negative, as required by Kabbalistic theory, amounts to mathematical proof of the correctness of the reconstruction.

Considering further the perfect match obtained with the placement of the gods, their grouping into meaningful triads and genealogies, and the identification of Assur with the winged disk, I feel very confident in concluding that the Sephirotic Tree did have a direct Mesopotamian model and that this model was perfected in the Assyrian Empire, most probably in the early 13th century B.C.

Being able to reconstruct this Tree, date it, and understand the doctrinal system underlying it, it has tremendous implications to the history of religion and philosophy which I will content myself with three concrete examples illustrating how the insights provided by the Tree are bound to revolutionize our understanding of Mesopotamian religion and philosophy.

THE TREE AND THE BIRTH OF THE GODS IN ENUMA ELISH

In Enuma elish, the narrator, having related the birth of Anu, mysteriously continues: “And Anu generated Nudimmud (= Ea), his likeness.” This can only be a reference to the fact that the mystic numbers of these two gods, 1 and 60, were written with the same sign, and indicates that the composer of the epic conceived the birth of the gods as a mathematical process. On the surface, of course, the theogony of Enuma elish is presented in terms of human reproduction. As the example just quoted shows, however, it did involve more than just one level of meaning.

In fact, the curious sequence of “births” presented in Tablet I 1-15 makes much better sense when it is rephrased “mathematically” as follows: “When the primordial state of undifferentiated unity (Apsu + Mummu + Tiamat, “0″), in which nothing existed, came to an end, nothingness was replaced by the binary system of oppositions (Lahmu and Lahamu)”‘ and the infinite universe (Anshar = Assur) with its negative counterpart (Kishar). Assur emanated Heaven (Anu) as his primary manifestation, to mirror his existence to the world.” Thus rephrased, the passage comes very close to Kabbalistic and Neoplatonic metaphysics.

Lines 21-24 of Tablet I of Enuma elish seem to describe the “birth” of the mystic number of Sin which can be derived from the number of Ea by simply dividing it by two. The irritation of Apsu caused by this play with numbers and the subsequent killing of Apsu and “leashing” of Mummu (lines 29-72) seem to be an etiology for the emanation of the third number and the establishment of the places of Ea and Mummu in the Tree diagram. The “birth” of Marduk, the next god in the diagram, is described in the following lines as expected. Marduk’s mystic number, like the numbers of all the remaining gods, can be derived from the preceding numbers by simple mathematical operations. The prominent part played by numbers both in Enuma elish and the Assyrian Tree of course immediately recalls the central role of mathematics and divine numbers in Pythagorean philosophy.

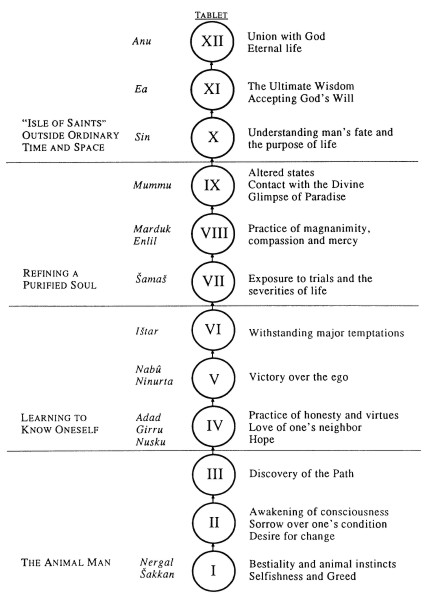

THE EPIC OF GILGAMESH

Looking at the Epic of Gilgamesh through Kabbalistic glasses, a new interpretation of the Epic can be proposed viewing it as a mystical path of spiritual growth culminating in the acquisition of superior esoteric knowledge (see fig. 12). The Path proceeds in stages through the Tree of Life, starting from its roots dominated by animal passions, the realm of Nergal (Tablet I); the names of the gods governing the individual stages are encoded in the contents of the tablets, and they follow the order in which they are found in the Tree, read from bottom to top. Tablet II, which has no counterpart in the Tree, deals with spiritual awakening; Tablet III outlines the Path; and Tablet IX describes the final breakthrough to the source of supernal knowledge.

Tablet IX also corresponds to the Sephirah Daath (Knowledge), which in the psychological Tree represents the gate to supernal knowledge, “the point where identity vanishes in the void of Cosmic consciousness before union with Kether”; passing through it is sometimes compared to spiritual death. The revelation of supernal knowledge, on the other hand, is described “in Jewish classical texts as a tremendous event, when the sun will shine with an overwhelming light. The act of acquiring supernal knowledge involves a change in both the known and the knower; it is presented as an active event, or penetration”. Compare this with the penetration of Gilgamesh through the dark passage of the cosmic mountain guarded by the Scorpion man and woman and his emergence to the dazzling sunlight on the other side. The beautiful jewel garden he finds there is the Garden of Knowledge; it corresponds to the “garden of God” of Ezek. 28:12 associated with wisdom, perfection, and blamelessness, and “adorned with gems of every kind: sardin and chrysolite and jade, topaz, carnelian and green jasper, sapphire, purple garnet and green felspar.”

The late version of the Epic consists of twelve tablets, the last of which is widely considered an “inorganic appendage breaking the formal completeness of the Epic, which had come full circle between the survey of Uruk in Tablet I and the same survey at the end of Tablet XI.” In reality, nothing could be farther from the truth. Without the twelfth tablet, the Epic would be a torso because, as we shall see, it contains the ultimate wisdom that Gilgamesh brought back from his arduous search for life.

That wisdom was not meant for the vulgar, and it is therefore hidden in the text. But the Epic is full of clues to help the serious reader to penetrate its secret. The refrain at the end of Tablet XI is one of these. Far from signaling the end of the Epic, it takes the reader back to square one, the Prologue, where he is advised to examine the structure of “the walls of Uruk” until he finds the “gate to the secret,” a lapis lazuli tablet locked inside a box.” “The walls of Uruk” is a metaphor for Tablets I-XI, ”the tablet box” is the surface story, and “the lapis lazuli tablet” is the secret structural framework of the Epic, the Tree diagram.

Once it is realized that the Epic is structured after the Tree, the paramount importance of Tablet XII becomes obvious, for it corresponds to the Crown of the Tree, Anu (Heaven), which would otherwise have no correspondence in the Epic. On the surface, there is no trace of Heaven in Tablet XII. On the contrary, it deals with death and the underworld, the word “heaven” (or the god Anu) not even being mentioned in it, and it seems to end on an utterly pessimistic and gloomy note.

When considered in the light of the psychological Tree and the spiritual development outlined in the previous tablets, however, the message of the tablet changes character. We see Gilgamesh achieving reunion with his dead friend Enkidu, being able to converse with him and thus to acquire precious knowledge from him about life after death; and what is more, he achieves this reunion in exactly the same way as he did in Tablet IX, by prolonged weeping and praying. In other words, the unique mystical experience recounted in Tablets IX-XI, there presented as something totally new and unusual, has in Tablet XII become a firmly established technique by which similar experiences can be sought at will.

In Jewish mysticism, such experiences are referred to as “ascent to heaven” or “entering Paradise” and regarded as tremendous events reserved only to perfectly ethical, perfectly stable men. The evolution of Gilgamesh into such a man is described in detail in Tablets I-VIII. In the Jewish mystical text Hekhalot Rabbati, the very concept of mystical “ascent to heaven” is revealed to the Jewish community as a revolutionary “secret of the world.” There can be no doubt whatsoever that this very secret, revealing the way to Heaven, was the precious secret that Gilgamesh brought back from his journey to Utnapishtim.

THE ETANA MYTH

The Mesopotamian myth of Etana is well known for its central motif, a man’s ascent to heaven on an eagle’s back. It has thus been classified as an “adventure story” or early “science fiction” containing the first known account of “space travel.” The eagle back ascent motif has been recognized to recur in Hellenistic, Jewish, and Islamic folk tales and legends and has also been connected with the Greek myth of Ganymede and the Alexander Romance. Much less attention has been paid to the tree inhabited by the eagle and the snake which figures so prominently in the second tablet of the myth.

Without going into unnecessary detail, it can be suggested here that the tree-eagle-serpent theme in Tablet II is an allegory for the fall of man and that the ascent to heaven described in Tablet III is to be understood as mystical ascent of the soul crowning an arduous program of spiritual restoration. Seen in this light, the myth becomes closely related to the Gilgamesh Epic in substance, and in presenting Etana as the first man to achieve the ascent, it forcefully contributes to the notion of the Mesopotamian king as the “Perfect Man.” The tree of Tablet II is Etana himself, whose birth its sprouting marks. The eagle and the serpent are conflicting aspects of man’s soul, the one capable of carrying him to heaven, the other pulling him down to sin and death.

In Christian symbolism, “The eagle holding a serpent in its talons or beak represents the triumph of Christ over the ‘dark forces’ of the world. In Indian mysticism, the bird Garuda likewise achieves its ascent to heaven in spite of the serpents coiling around its head, wings, and feet. In the Etana myth, the eagle plays two roles. At first, it is “an evil eagle, the criminal Anzu (var.: criminal and sinner), who wronged his comrade”; as such, it parallels the eagle inhabiting the huluppu tree in the Sumerian Gilgamesh epic, which is explicitly called Anzu. Later, however, having suffered and been rescued by Etana, it carries the latter to heaven. The evil aspect of the bird corresponds to the natural state of man’s soul, which, despite its divine origin, is contaminated with sin (see Enuma elish VI 1-33 and Lambert and Millard, Atrahasis, p. 59). The second aspect of the bird corresponds to the soul of a “purified” man. The “tree” itself is marked as sinful by its species (the poplar), associated with Nergal; Bel-sarbe “Lord of the Poplar”. This accords with Ebeling, Handerhebung, p. 114:9, which explicitly states that mankind is “entrusted to Nergal,” that is, under the power of sin.

The deal struck by the eagle with the serpent marks the beginning of Etana’s moral corruption as king. Ignoring the voice of his conscience, he becomes guilty of perfidy, greed, and murder; for this, he is punished. Etana’s voice of conscience is the “small, especially wise fledgling” of II 45 and 97. Note that the theme of bird’s nest with the young (taken over from the Sumerian Lugal-banda epic) also plays a role in Kabbalah, where it is explicitly associated with self-discipline and wisdom.

The serpent attacks the eagle, cuts off its wings, and throws it into a bottomless pit. This is an allegory for spiritual death; the same idea is expressed by the childlessness of Etana, to whom the narrative now returns.

Etana’s realization of his condition is the beginning of his salvation; from now on, he appears as a person referred to by his own name. Admitting his guilt and shame, he prays for a “plant of birth” (that is, a chance for spiritual rebirth) and is guided to the path that will take him there.

The spiritual meaning of the prayer (concealed under the “plant of birth” metaphor) is made clear by the preceding prayer of the eagle (II 121-23): “Am I to die in the pit? Who realizes that it is your punishment that I bear? Save my life, so that I may broadcast your fame for eternity!” In the late Turkish version of the myth, the bird rescues the hero from the netherworld.

The path leads him to the mountain where he finds the eagle lying in the pit with its wings cut, a metaphor for the imprisonment of the soul in the bonds of the material world. Complying with the wish of the eagle, his better self, he starts feeding it and teaching it to fly again, an allegory for spiritual training and self-discipline. It takes eight months to attempt the first ascent to heaven, which fails because Etana himself is not ready for it.

The second ascent, better prepared, is successful and takes Etana into a celestial palace where he, having passed through several gates, finds a beautiful girl sitting on a throne guarded by lions. All this is so reminiscent of the terminology and imagery relating to the ascent of the soul in Jewish mysticism that mere coincidence can be excluded. The several heavens and heavenly palaces through which Etana passes are commonplace in the Hekhalot texts and later mystical literature. The girl seen by Etana is the Shekhinah, the Presence or Beauty of God. Etana’s fall from the heavens has ample parallels in Kabbalistic literature, where the ascent is considered a dangerous practice and the return to a normal state referred to as being “thrown down like a stone.”

The heavenward ascent of Etana is already attested on seals from the Akkadian period (ca. 2300 B.C.) and thus antedates the earliest Hekhalot texts by more than two and a half millennia, and the mystical experiences of 19th century Kabbalists by more than four thousand years. In saying this, I do not want to stress the antiquity of the “ascent” phenomenon in Mesopotamia. The point I wish to make is that, against all appearances, Mesopotamian religion and philosophy are not dead but still very much alive in Jewish, Christian, and Oriental mysticism and philosophies. The Tree diagram provides the key which makes it possible to bridge these different traditions and to start recovering the forgotten summa sapientia of our cultural ancestors.

Pingback: The Secret Life of Trees - Everyday Anthropology